My Fifth Stop on a Pilgrimage of Hope

Introduction

We are still in Capernaum and for whatever reason, I recall experiences of alerting students to the reality of Jesus’ life as a young boy and the journeys he made with his parents and other members of the Nazareth community to the city of Jerusalem for religious festivals. It was a journey made on foot and it took at least three days to walk about 125 kms.

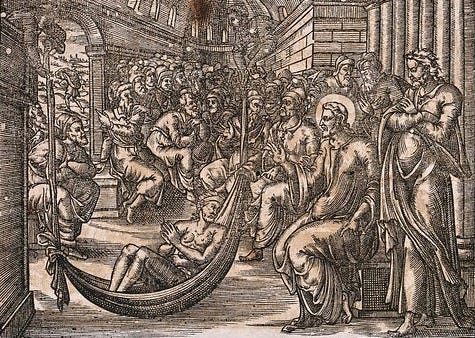

It is not so much the faith of those who are suffering as it is the faith of those who respond with empathy to their plight. Such is the message of the story in Mark’s Gospel of the four friends who hauled their sick and suffering mate up on the roof of the place where Jesus was staying and after making a hole in the roof, lowered him down into the room, right in front of Jesus (Mark 2:1-12).

Of faith and compassion: hope

This is one of my favourite stories from Mark’s Gospel. Jesus heals the paralysed man not because of his faith but because of the faith of his friends, whose commitment to their ailing friend and their problem-solving is to be admired and imitated through practising the spiritual and corporal works of mercy.

Through Jesus, the God of Compassion works wonders. Jesus holds a view of the world in which there is no place for “the letter of the Law,” which brings him into conflict with the teachers of the Law. He is one with the Father in heaven, for whom the spirit of the Law is everything. And the spirit of the Law is forgiveness, not condemnation.

Created in the image and likeness of God, we are God’s sons and daughters. It is through faith that our share in divine life is restored, which had been lost through sin. It was the faith of the paralysed man’s friends that led to his reconciliation with God, a demonstration of the gracious love and mercy of God, through Jesus.

There is a bond between the faith of his friends and their hope in God’s mercy. That bond, or relationship, empowers them to act audaciously. Pope Benedict XVI expresses this well when he writes in his encyclical Spe Salvi (2007) that the Christian message “makes things happen and is life-changing” (#2), suggesting that hope is not simply a belief about the future but something transformative of the present. Similarly, in his “Urbi et Orbi” message, delivered on Easter Sunday, Pope Francis insists that “[H]ope is not an evasion, but a challenge; it does not delude, but empowers us.”

Hope empowered the paralysed man’s friends. Their faith transformed them. They found a solution and hauled their friend onto the roof of the house where Jesus stayed and lowered him down through the hole they made in the roof.

Joseph Cardijn, a hope-filled leader

As I reflected on their faith, courage and determination, I was reminded of Cardinal Joseph Cardijn (1882-1967) and his commitment to the young workers of the world. He was still a teenager and attending a minor seminary near where he had grown up, when he discovered that his former classmates had abandoned the practice of their faith so soon after leaving school. The shock of this discovery and the premature death of his father led him to make a commitment to work for the wellbeing of young workers and to form them as apostles of the working class.

Many years later, in 1948, he delivered a series of lectures at the annual congress of the Young Christian Workers Movement (YCW), which had grown out of his efforts to form the young workers in the parish of Laeken, on the outskirts of Brussels, where he had been sent as the assistant parish priest in 1012. In the first lecture of a series he titled “The Hour of the Working Class”, he said:

“To be apostles, they must realise that with the temporal betterment of the working class, there must also be achieved simultaneously its eternal spiritual wellbeing.”

The efforts of the paralysed man’s friends are an example of what Catholics know as the corporal works of mercy. They knew that Jesus would be able to heal their friend and they did not allow a crowded house to stop them from presenting the paralysed man to him. Jesus responded with actions that addressed both the temporal and eternal destinies of the man lowered in front of him, and of all who came after him to be made whole again.

All this was reflected in the work of Cardinal Joseph Cardijn, who taught the young workers in the movement he established that their dignity, which is God-given - all people are created in the image and likeness of God - signifies the divine life God shares with them. Like the friends of the paralysed man, they are to respond to both the temporal and eternal destinies of their fellow workers.

And into my backpack …

Just as the paralysed man was transformed through his encounter with Jesus, we, too, are called to play our part in the transformation of our families, our friends and the society in which we live.

And so I place in my backpack the realisation that to be a responsible human person, I must consider not only the temporal needs of those around me, but also their eternal destiny. Just as the four friends acted as instruments of salvation in bringing their ailing friend to Jesus, then I, too, need to accept the responsibility of being an instrument of salvation as God intends.

I recall that as a child I learned about the corporal and spiritual works of mercy. And so I place in my backpack the commitment to re-visit what I was taught many years ago … and I know I will find them on the wall of the meeting room in my parish church. I also know that Google will find them for me when I ask!

Image source: Image of a woodcut depicting Jesus healing the paralysed man lowered through the roof, Look and Learn, CC by 4.0